To: MAES/AU Students

From: Kaat Veeckmans, Chloë Coremans, Lotte De Schryver, Nickie Vandenbrouck, Tiago Carvalho, and Connor Murray

Date: March 13, 2022

Subject: NATO Burden-Sharing Policy Memorandum

1. NATO Background (By Kaat Veeckmans)

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) was founded as a transatlantic political and military alliance of 30 allies on both sides of the Atlantic to ensure peace after the European continent was ravaged by two major conflicts in 30 years and amid the threat of Soviet expansion. The purpose of the alliance is to “guarantee the freedom and security of its members through political and military means.” From a political perspective, NATO achieves this goal by promoting democratic values and enabling members to consult and cooperate on defense and security-related issues. From a military perspective, NATO mainly focuses on the peaceful resolution of disputes and military crisis-management operations as well as providing collective defense for its members.

In order for NATO to be able to carry out its objectives, the alliance relies on its members to provide adequate funding and contributions of troops, materials, and capabilities. All member states make different nominal contributions based on their gross domestic product (GDP), which results in some countries making bigger contributions than others. NATO defines this as burden-sharing, or “the relative weight of the distribution of costs and risks across Allies in pursuit of common goals.” However, the reality of burden-sharing often comes down to “large, rich allies shouldering the defense burden of the small, poor allies by providing the latter with a relatively free ride.” This imbalance has sparked the debate on measures needed to be implemented in order to guarantee a fairer divide in costs and risks while also not putting countries unable to contribute as much at a disadvantage.

The lack of fairness in burden-sharing has caused tensions within the alliance, especially between the United States (U.S.) and the European member states (MS). The imbalance in contributions has existed for many years, proof of which can be found in the 1970 when the U.S. accounted for just under 75% of NATO’s defense spending, while the next largest allies (Germany, France and the United Kingdom) each assumed less than six percent of NATO’s finances. This is why the U.S. has “long urged its European Allies to step up their defense investments and increase their capacity to shoulder the burden of the Euro-Atlantic security guarantee.”

2. Contemporary Relevance of Burden-Sharing to Transatlantic Relations (By Chloë Coremans)

NATO’s founding principle of collective defense allowed the alliance to more effectively protect itself, especially with the guarantee of U.S. support. Furthermore, the alliance has always been based on trust and collaboration as most, if not all, members contribute to a variety of common norms and values, such as the peaceful resolution of conflicts, individual liberty, human rights and the rule of law. After the Cold War, the threat of the Soviet Union disappeared and Russia was not seen as a prominent aggressor to Europe and its allies. However, President Vladimir Putin’s increased aggression culminating in the current developments in Ukraine highlights that the threat never truly disappeared. As the opposition to communism - once the leitmotif behind the transatlantic cooperation - disappeared, NATO had to shift its focus to new and rapidly emerging security threats, e.g. terrorism. The NATO allies on either side of the Atlantic have often approached these emerging challenges differently. These differing stances have been exploited by important geopolitical players such as Russia and China, especially given increased domestic polarization on both sides of the Atlantic.

As was alluded to in the introduction, current tensions among NATO allies largely center on a U.S. perception of insufficient defense contributions from Europe, and European frustration with U.S. unilateralism. For example, under President Bill Clinton, the United States conducted NATO air strikes in the Balkans, dismissing Russian President Boris Yeltsin's protests and amid apprehension from the Europeans. President George W. Bush dismissed European protests when he opted not to ratify the Kyoto Protocol. Despite France and Germany threatening opposition to the Iraq War in the United Nations Security Council, Washington went ahead. Finally, the centerpiece of U.S. President Barack Obama's foreign policy early in his presidency was the important pivot to Asia, which necessarily implied less focus on Europe.

Furthermore, President Donald Trump rattled NATO’s underpinnings even before he was elected, once referring to the alliance as “obsolete.” His many remarks foreshadowed the turbulent period the transatlantic alliance would go through throughout his presidency. In contrast to his predecessor, current U.S. President Biden stressed that he will further strengthen all aspects of the NATO Alliance in one of his remarks on the recent developments in Ukraine and Russia. Furthermore, skepticism towards NATO is not solely limited to the Americans. Countries such as France are pushing for strategic autonomy in the security and defense domain as they fear they can no longer rely on the U.S.’s commitment to the NATO alliance. French President Emmanuel Macron once labeled the alliance as “brain dead” - a statement condemned by former German Chancellor Angela Merkel.

However difficult the negotiations surrounding transatlantic burden-sharing may be, it remains a valuable aspect of the cooperation. In 2021, NATO’s Sub-Committee on Transatlantic Relations drafted a report, which included “ways to rejuvenate the transatlantic bond and to seek fairer burden-sharing in the context of the NATO 2030 agenda and the revision of NATO’s Strategic Concept.” The report concluded that in the future a more 'political NATO' should be encouraged by investing in more political dialogue in order to enhance the convergence of positions among the 30 allies.

3. Areas of Transatlantic Divergence (By Tiago Carvalho)

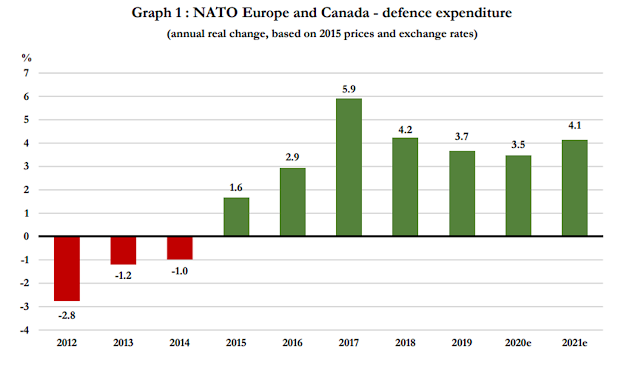

Areas of divergence between transatlantic actors have always been present in the relationship of the defensive military alliance, and the contribution to the budget issue is timeless. At the 2014 Wales Summit, NATO member states (MS) agreed to contribute at least two percent of their GDP to defense spending. Of that overall two percent, 20 percent would go to development and procurement of military equipment and two percent to defense research and technology by 2024.

Since 2014, when only three countries met the two percent goal, seven additional allies have reached the threshold. Also, considering the 20 percent goal for spending on equipment, only seven countries met it in 2014, and in 2021 24 countries are in compliance. This increase in contributions to the budget was not by chance, as the illegal annexation of Crimea by Russia put the organization on alert and drew attention to the immediacy with which the European allies needed to step up. That immediacy has been further underscored by the events of the past three weeks.

Nevertheless, there are other areas where MS do not agree and there are different points of view to consider, “political divergences within NATO are dangerous because they enable external actors, and in particular Russia and China, to exploit intra-Alliance differences and take advantage of individual Allies in ways that endanger their collective interests and security.” The focus of U.S. foreign policy in the Indo-Pacific region to deal with the rise of China has led Europeans to worry that the U.S. commitment to European security will diminish. In turn the Americans think that the Europeans will shirk their collective responsibilities or follow the path of strategic autonomy (which is already being developed in some way, but can be seen as a European pillar of NATO).

Yet, Americans also argue that Europeans are taking advantage of their military protection and military deterrent power, while Europeans respond that much of the U.S. spending included in burden-sharing comparisons went to European mission expenditures where many European MSs opposed. In this sense, MS such as France and Germany perceive the American military presence in Iraq, Syria, and elsewhere as provocative rather than protective. This diminishes trust between allies and opens space for internal differences. It also shows that there are differences in threat perception and willingness to share the burden, as they are shaped by geopolitical position, military capabilities, economic capacities and foreign policy objectives. The treatment of China will also continue to be a point of contention, especially given the heavy trade flows between China and Europe. Thus, these divergences suggests that security framing is different between transatlantic partners and strategies that may be considered useful to the U.S. may have limited utility on the other side of the Atlantic.

4. Areas of Intra-European Divergence (By Lotte De Schryver)

Within Europe there are also disagreements on the burden-sharing issue. Firstly, the European defense industry is a sector that is closely linked to the U.S., however in recent years Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO) projects have aimed to strengthen and empower the European industry and the cooperation between its members. It is in this sense that divergences arise, as some European MS seek industrial autonomy, while others are closely linked to the U.S. within the defense industry, their leaders feel that following this path would not help them. Furthermore, this type of policy encourages the European Union (EU) MS to seek to elevate their industrial interests by putting aside possible transatlantic cooperation. On the other hand, Europeans are asked to share the burden, but not to wreak havoc on American industrial interests. This in itself is contradictory and forces Europeans to choose between maintaining close ties with the Americans in this sector which would undermine the technological and industrial base or seeking cooperation on the continent in this sector which would deteriorate the relationship with the U.S.

There are also differences in terms of which path to take in relation to the future of European security, whether Europe should pursue strategic autonomy without NATO or autonomy in complementarity. The approaches have varied from government to government. There are some states that are not willing to take the risk of investing in European autonomy, because they are so threatened by Russia that American protection and deterrence is essential for them, while countries like France, lead the idea of investing in a European defense union in order to assume more responsibility for defense in Europe and leave the U.S. free to focus on the Indo-Pacific.

Furthermore, Europeans lack a shared strategy and culture that define what a threat is. However, this is not easy to achieve as there are so many diverging national interests and different views on how to share the burden. While for central and eastern states Russia is a threat, the foreign policy white paper for southern states does not mention Russia as such, and countries like Germany will always take into account commercial interests in relation to this country before mention as a threat in an official document.

To conclude, the lack of a common European vision, undermined by different conceptions of threats, responsibilities, dispositions to spend money and various national interests is something that makes a common European position for the sharing of responsibilities in the NATO framework difficult.

5. Proposals and Recommendations (By Connor Murray & Nickie Vandenbrouck)

Although the percentage goals have helped increase defense spending in Europe overall, they can be an arbitrary threshold to evaluate the level of participation within the transatlantic partnership. Denmark, for example, according to the 2% benchmark, fails “to meet either target, yet still manage to outperform most other allies in terms of capabilities and contributions.”

The percentage goal fails to take into account the vast differences in economic and military capabilities within Europe and also fails to consider how allies can most productively contribute to transatlantic security. This phenomenon exposes a great deficiency in NATO’s management capabilities, which could benefit from a more tailored approach.

Clearly, burden-sharing “bullying,” which peaked during the Trump Administration, is the wrong way to approach this debate, but criticisms about “European free-riding" are not entirely unfounded either. That being said, varying levels of participation do not undermine the overall value of the alliance. For example, actions taken by NATO do not always have to include the entirety of the alliance. Indeed, a more flexible approach that includes a subset of allies may be preferable to a whole-alliance approach that requires unanimity of support.

Recommendation 1: Create flexibility within NATO’s organizational burden-sharing framework to allow for allies to contribute without fixating on percentages. The need for allies, especially those in Europe, to pull their weight is clear but being more nuanced in the approach to take domestic situations and COVID-19 recovery into account could be a significant step to stabilize and secure the alliance’s existence in the long term.

There is a clear and mutual lack of trust within the Transatlantic partnership. The U.S. feels like Europe is not pulling its weight, while Europe grows weary of the volatility of U.S. leadership and their ever-shifting security focus now directed at the Indo-Pacific and China.

In truth the erosion of the Transatlantic relationship has much more to do with “domestic dynamics on either side of the Atlantic.” Europe, but particularly the EU remains divided and is plagued by one crisis after another, while the U.S. is caught in an “increasingly dysfunctional political system” as the gridlock between Republicans and Democrats translates heavily into foreign policy as it continues a growing trend towards isolationism.

It is imperative for the Transatlantic trust to heal that the U.S. reaffirm their commitment to European Strategic Security and Europe becomes a more active participant to its own strategic defense, both in terms of increasing individual, national military capabilities, as well as ensuring EU-wide cooperation.

Recommendation 2: The Biden Administration should take additional public steps to assure its European allies of the U.S.’s continued commitment to Europe. Despite the desire of policy makers in the U.S. to shift their focus to the Indo-Pacific, Europe must be assured of ongoing U.S. support. Similarly, both sides of the transatlantic partnership face threats of democratic backsliding and must redouble efforts to ensure that the basic values of NATO are protected otherwise risking the alliance’s legitimacy.

As our colleagues mentioned before, a big issue that stands in the way of EU-wide cooperation in defense lies with the diverging security concerns within MS and how they relate with the debate surrounding the concept of strategic autonomy. The idea of a “European defense autonomy linked to the EU” that has been championed by leaders, such as President Emmanuel Macron of France, may be “just as absurd as Trump’s emphasis on burden-sharing bullying.”

Considering that EU member states have clear differences they need to address (see Poland & Hungary) and they have the understandable desire of Eastern European states to keep the U.S. on their good sides to deter Russia, it is realistic to say there won’t be a common agreement on defense for the EU any time soon. Not to mention the time it would take to realize such a project to form should it be agreed upon after all.

Abandoning the “European Option Fallacy” would encourage EU member states to no longer view strategic autonomy as a threat to the existence of NATO, but rather as a way to kill two birds with one stone. By increasing its defense autonomy - both on the national and EU-level - European States can more effectively contribute to NATO defense all the while leaving more space for the U.S. to pursue other goals (without, of course, abandoning their security interests in NATO).

Recommendation 3: Further strengthen EU-NATO cooperation to possibly even include formal integration to allow for European strategic autonomy to exist within the EU-NATO framework.

Russia’s unprovoked invasion of Ukraine has given NATO partners a golden opportunity to revitalize and strengthen the collective defense of Europe. Political will to increase defense spending and unity among the alliance is at a high point not seen in recent history. NATO Defense Ministers will meet in Brussels on March 16, 2022. While this meeting likely will focus on the ongoing crisis, ministers would be remiss to not consider re-evaluating the strong focus on funding as a measure of burden-sharing.

Recommendation 4: Use the momentum of solidarity with Ukraine to reinvigorate NATO and its allies toward the common goal of European safety and security. By safeguarding this stability, NATO will also lay the groundwork for potential global action and the shift toward priorities outside of continental Europe that still have an effect on European security.

Comments

Post a Comment